Why the Growing Reliance on Adjunct Faculty is a Bad Thing

Choosing between colleges? Here are some questions to ask to weed out the schools that may be neglecting their academics.

If you’re choosing a college, there’s a trend you need to know about. An increasing number of classes, particularly for undergraduates, are taught by part-time instructors.

Sometimes they’re just as qualified as the full-time faculty. Sometimes they’re not. But they’re always paid a good deal less. Meaning they’re probably trying to cobble together an income from more than one gig. Meaning they’re less available to any one set of students.

You’re less likely to have a great academic experience if your college has outsourced a big chunk of its teaching.

A Concerning Trend

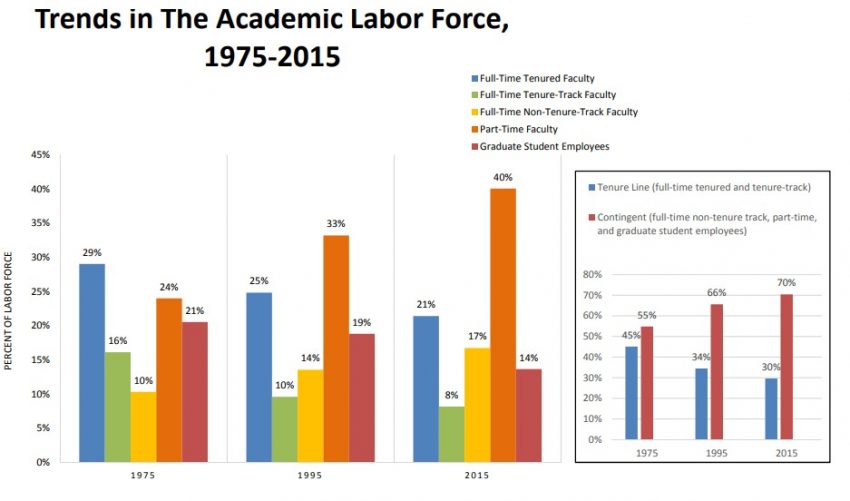

Here’s the data from the American Association of University Professors:

Notice how the blue and green bars are getting shorter while the orange bars are getting larger. The green bars represent faculty on track to earn tenure, typically over a seven-year process. The blue bars represent faculty who’ve already earned tenure. These categories, combined, represented 45% of all faculty in 1975, but just 29% in 2015.

These data are conservative. A 2013 study from the Pullias Center for Higher Education at USC found a much larger decrease from 78% to 34% (1969 to 2009).

But let’s use the more conservative 45% to 29% drop. That’s still a big drop! In the same time frame, the part-time faculty grew from 24% to 40%. Not only do part-time faculty (adjuncts) lack benefits, their pay is low given the demands of the work. It ranges from about $1,500 per course at a community college up to $8,000 per course at a prestigious university in a high cost-of-living area.

Let’s say its $5,000 per course. You’d have to teach 10 courses per year to earn $50,000. Before taxes. Without benefits. And probably from multiple schools, since no one school would give you that much work. If they did, they’d have to give you health insurance. A 2014 congressional report found that 89% of adjuncts worked at more than one college. Many colleges set their caps right below the limit.

The yellow bars represent full-time non-tenure track faculty. These folks have job titles like “visiting professor” or “lecturer.” On the plus side, they work full-time for one college. They get health benefits. And their salaries are higher than adjuncts. On the down side, they’re typically paid less than a high school teacher. And they share with their part-time brethren the status of being “contingent.” That means they work on a year-by-year basis, lacking job security.

Are Christian Schools Better?

Christian schools have more reasons than others to oppose this trend towards a greater reliance on adjuncts. The low pay scale is unfair, given what you’re asking in exchange. It devalues the work of teaching, creating a race to the bottom effect. There’s a bait-and-switch element to saying, “Look at the wonderful faculty on our website. Oh, but the lion’s share of your classes won’t be taught by them.” And it’s harder to connect academic learning to moral and spiritual formation if a large segment of the instructors are working multiple jobs to make ends meet.

That said, I don’t know whether Christian schools are better than their secular counterparts at resisting this trend. I would hope they are.

Two Caveats

Colleges sometimes land great instructors who are only available as adjuncts or visiting professors. These folks already have a day job that pays the bills. An all-around win in these cases. Plus, it’s not possible for every course to be taught by a tenure-track faculty. Given their other duties to the college, tenure-track faculty (like adjuncts) work best when they aren’t spread too thin. Adjuncts provide much-needed flexibility. And adjunct work can be a stepping stone into a tenure-track role.

Still, the flexibility argument is overused. For example, lots of freshman courses — in writing, math, and science — are taught by contingent faculty. But enrollment needs for these courses are among the easiest to predict. Moreover, the quality of teaching in these courses can make all the difference in whether freshmen make it to graduation.

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) recommends that no more than 15% of courses at a university, and no more than 25% of courses within any one department, be taught by non-tenure track faculty. That’s a high bar these days, but a good target.

Second caveat: Some adjuncts are motivated to prove themselves, while some tenured faculty are lazy and therefore lousy teachers. The solution is two-fold. One: Open more tenure-track positions so that quality adjuncts can land such roles if that’s their ambition (as it is for many). Two: Tack on a tenure review or renewal process, perhaps every 5-7 years, to provide a measure of accountability for the old-timers.

Cost Savings?

We know that a growing reliance on adjuncts helps colleges save money. But does that mean overall costs go down? Not necessarily. According to a study by the Delta Cost Project, the cost savings from the increased use of part-time faculty were “offset by rising benefit costs and increased hiring of administrative staff.” A variety of research studies have found that administrative positions have grown at a faster rate than the number of faculty positions, let alone tenure-track slots.

Other places that absorb the funds include facilities, recruitment/marketing, and nonacademic student programming.

What to do?

Before choosing a college, ask questions like these:

(1) What percentage of my child’s courses will be taught by non-tenure track faculty? How about part-time faculty or graduate students?

You’re not looking for zero. But it shouldn’t be 50%, either.

(2) What are the minimum qualifications to be a part-time instructor?

Do they need to have a master’s degree? How about a bachelor’s degree? Don’t laugh. It happens! Might bio statements for adjuncts be available online? These would list their credentials.

(3) Are non-tenure track faculty available to meet with students outside of class?

You can’t have office hours without an office. A shared office is better than nothing.

(4) Do students evaluate their professors? Even the adjuncts? How are these evaluations used?

I’ve heard of schools hiring the same adjunct semester after semester, even though the students can’t understand him. Why? They can’t find anyone else to teach the (required) course. Not good.

(5) How have the number of administrative and staff positions at your college grown over the last 10-20 years, relative to the number of tenure-track faculty positions?

This is something of a “third rail” issue. But hey, why not ask? You can also poke around the school’s website to see how many Deans and Assistant Vice-Presidents have odd-sounding job titles. Ask what they actually do.

Informed Customers Make a Difference

You may wonder “Why are schools spending all this money on non-academic stuff, while hiring fewer permanent faculty?” Colleges are responsive to markets. They’ll do what they think is necessary to attract students. Frankly, colleges with nice cafeterias, recreation centers, and lots of non-academic programming have less trouble attracting students. So they’d be dumb not to spend on these things.

It’s a matter of balance. If having great faculty matters to you, make sure the academic side isn’t being neglected.

Dr. Alex Chediak (Ph.D., U.C. Berkeley) is a professor and the author of Thriving at College (Tyndale House, 2011), a roadmap for how students can best navigate the challenges of their college years. His latest book is Beating the College Debt Trap. Learn more about him at www.alexchediak.com or follow him on Twitter (@chediak).