Fasting for Body and Soul: A Prolonged Fast During Holy Week

This is the thirteenth piece in a series on how to develop a fasting lifestyle. Read the entire series here.

We have now entered Holy Week, when we remember the last days of Jesus’ ministry before He was crucified.

Many of us have given something up during Lent, as a sort of “fast.” For most of history, most Christians have also fasted from food in some way. Details vary. Eastern Orthodox Christians have subsisted on a vegan diet for most of these forty days of Lent. Catholics will eat less than they normally do on Good Friday. Many Protestants will do the same.

If you’ve been following this series on fasting, though, you won’t be surprised that this week, I’ll suggest we do more than that.*

You now have what it takes to fast more than twenty-four hours. And if there’s ever a good time during the year to do that, it’s Holy Week. It’s the summit of the Christian Year, and it ends with a proper feast!

Last week, you ate very little on three non-consecutive days. The week before that, you tried intermittent fasting. And for two weeks before that, you worked to turn on your fat-burning metabolism, which you need during fasting.

You now have what it takes to fast for more than twenty-four hours. And if there’s ever a good time during the year to do that, it’s Holy Week. It’s the high point of the Christian Year, and it ends with a proper feast!

More Than 24 Hours

Let’s call any water-only fast that lasts more than 24 hours a “prolonged fast.” As we’ve already learned, you can do 23-hour fasts and still eat plenty of food for an hour every day. So, the big hump to get over is a second night without eating.

If you stop eating at 7:00 PM on, say, Thursday, fast all day Friday, and eat again on Saturday morning, you’ve made it 36 hours. If you make it to Saturday night, that’s 48 hours. Sunday morning? That’s 60 hours. If you go from Thursday morning to Sunday morning, that’s a full 72 hours.

Which one you try is up to you.* Everyone is different. Pray about it. But if you’re able to do at least a 36-hour fast, you should have what it takes to make fasting part of your lifestyle from now on.

You should read about the complications and dangers from this moderate skeptic of prolonged fasts before you start. Also, read these comments from physician and fasting guru Jason Fung.

Won’t I Keep Getting Hungrier?

There’s one myth that I want to debunk, though, since it keeps most people from even considering prolonged fasts. No, you won’t keep getting hungrier and hungrier.

It has to do with ghrelin, the hormone that tells your body to eat. If you’ve ever found yourself missing breakfast and lunch, and then scarfing down old donuts you found in the lunch room, you might imagine that ghrelin goes up the longer you go without eating. If you were to map ghrelin over time, with ghrelin levels on the y axis, and time on the x axis, you might guess that the ghrelin line would slope ever upward.

Like this:

Not how it really works.

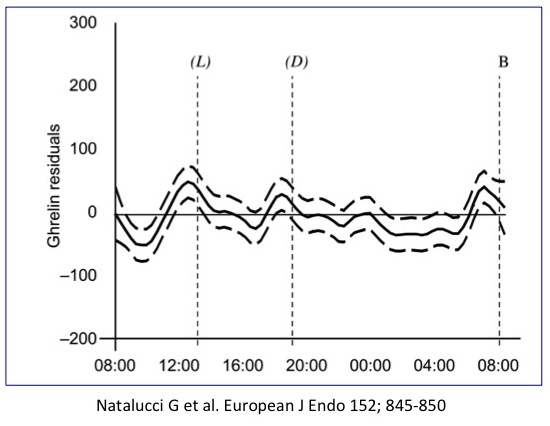

But that’s not what happens when you’re fasting. The hormone goes up and down with your body’s circadian rhythms (your pattern of waking and sleeping), and your normal eating schedule. In one study of subjects fasting for 33 hours, ghrelin was lowest at 9 am, when they’d gone all night without eating. Then the levels went up again at lunch and dinner time. But then ghrelin subsided until the next morning, when it got about as high as it did at lunch time the day before.

Here’s the graph of the results of the study:

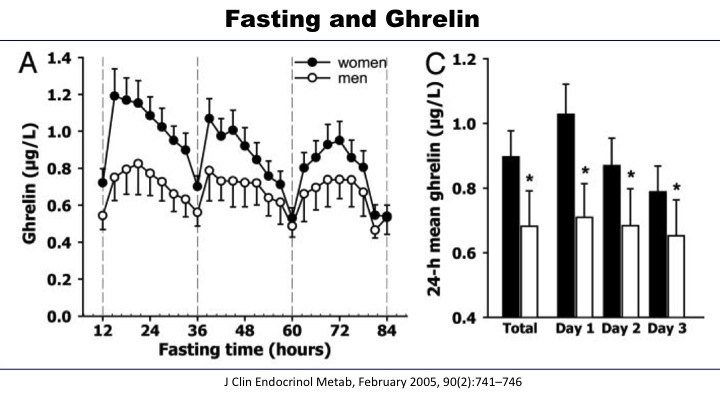

Another study followed fasters for 84 hours. It found that ghrelin levels for both men and women went up and down with the nighttime and daytime, but slowly declined over the course of three days.

Almost anyone who does a prolonged fast will tell you the same thing. The second day is usually the hardest. And then hunger symptoms start to wither away, until your body decides it really needs food. (Read Dr. Jason Fung’s great analysis of these studies here.)

So, if you make it forty-eight hours, seventy-two hours might not be all that big a deal.

The Plan for the Next Few Days

If you’re going to do a 36- to 72-hour fast before Easter Sunday, then you should get your fat-burning metabolism going full blast before you start. Here’s what I would suggest. Between now and the start of your fast, eat a strictly ketogenic diet: high fat, moderate protein, very low carb. Limit your carbs to low-glycemic veggies. And eat all your meals in an 8- to 12-hour window. This will keep your insulin and blood sugar levels low. And your body will already be running on ketones before you start your prolonged fast.

Again, remember that you’ll need to drink a lot of water and supplement with electrolytes throughout.

Don’t Forget: Both Body and Soul

Many of the health benefits of fasting can be had by following the methods we test drove in the first four weeks. Indeed, about 70% of the insulin drop you’re likely to get will happen around 24 hours into a fast. But insulin levels can continue to drop for a solid 72 hours. At that point, you’ll be deep into ketosis. And you might just stay there as long as you have plenty of body fat to burn.

There are some other, more speculative perks to prolonged fasts.

But don’t focus on those now. This is Holy Week! You should use all the extra time for spiritual benefit. Many churches have Holy Thursday and Good Friday services, Stations of the Cross and other events. Attend all of them. Read the gospel’s passion narratives over and over. Pray for moral and spiritual revival — for your family, your church, your country, and the world.

And remember: Sacrifice and the cross are not the end of the story. But we must all pass through them.

Next up: Breaking your Lenten Fast with an Easter Feast

*I’m referring to those who are healthy enough to do it. If you have an eating or metabolic disorder or are taking drugs for high blood pressure or diabetes, talk with your doctor about fasting.

Jay Richards is the Executive Editor of The Stream and an Assistant Research Professor in

the Busch School of Business and Economics at The Catholic University of America. Follow him on Twitter.