The Opioid Crisis: Why It’s Getting Worse

Opioids — drugs like oxycodone, heroin and fentanyl — killed thousands of people in 2014 and 2015. The nationwide addiction problem was a major point of agreement for both candidates, and played a major role in a bipartisan bill signed by President Barack Obama before he left office. These drugs are being blamed for a skyrocketing number of overdose deaths in recent years, including a quadrupling of deaths from heroin since 2010.

Opioid is the broad name for drugs that block pain signals from reaching the brain by binding to opioid receptors in the body. Available only by prescription, they are used to reduce moderate to severe pain. They can also be highly addictive when abused.

Why did they become a national epidemic?

Introduced Legally

Unlike the crack cocaine that led to another epidemic 30 years ago, opioid overuse first became an epidemic through legal means. Doctors began to prescribe the drugs to increasing numbers of patients to reduce pain. Over 300 million prescriptions, equaling a $24 billion industry, were issued in 2015 in the U.S. alone, one expert told CNBC, nearly equaling the U.S. population. About 80 percent of those who use opioids worldwide live in the United States.

A recent survey of opioid addicts and their family members from the Kaiser Foundation found 98 percent claim to use the drugs to control pain. However, about one-third admit that they take the powerful drugs to get high.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the National Institutes of Health, the factors likely to have contributed to the problem include:

drastic increases in the number of prescriptions written and dispensed, greater social acceptability for using medications for different purposes, and aggressive marketing by pharmaceutical companies. These factors together have helped create the broad “environmental availability” of prescription medications in general and opioid analgesics in particular.

One study found that 91 percent of those who had overdosed on prescription painkillers could get another prescription after overdosing. Many users rely on several doctors to get prescriptions in order to avoid any doctor limiting access to pills.

2015 saw a record number of people die from overdoses. Recent Centers for Disease Control data shows that the vast majority of those who overdosed in 2014 and 2015 were white, with a plurality of the deceased around middle-age (see chart below):

The Result: A Rise in Heroin Overdoses

While the opioid crisis has developed over 15 years, heroin use has especially skyrocketed since 2010. The heroin epidemic was likely birthed by addiction to prescription opioids. About 80 percent of users were previous prescription drug users as of 2011, according to the CDC.

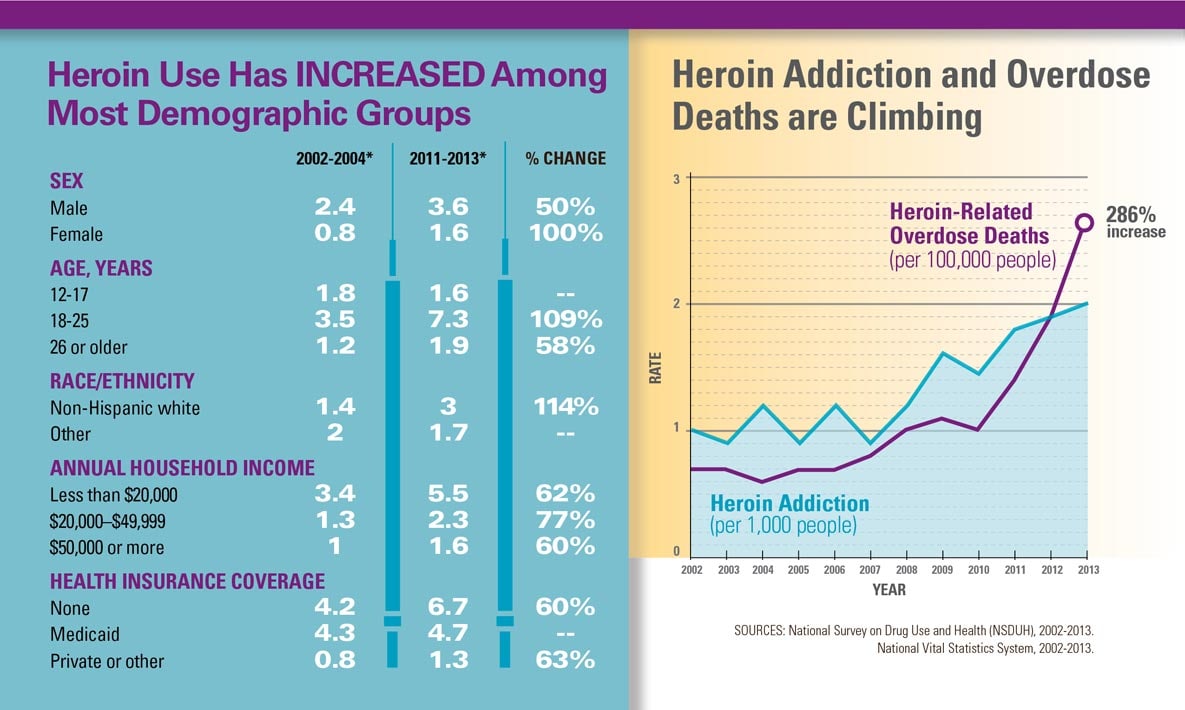

As shown by the below data provided to The Stream by the White House’s drug office:

What started as a crackdown on “pill mills” in Florida helped launch street-level heroin addiction, The Guardian reported. With authorities attempting to stop doctors from simply issuing pills to people who claimed to be in pain — some having driven hundreds of miles to get the drugs — heroin became the go-to drug for many, with an enormous rise among young adults, according to a government report analyzing drug use from 2002 to 2012.

Describing one young prescription opioid addict, The Guardian noted, “When a government crackdown curtailed his supply of pills, [James] Fata turned to readily available heroin to fill the void.” He told the newspaper that “the pills were hard to get. They got to be very expensive. Heroin is cheap. Almost everyone that I was close to, anybody that was doing pills with me, typically they would at least get to the point where pills were not an option. You were either snorting heroin or shooting heroin.”

Cheaper than most other opioids, heroin provides the kind of high necessary to reduce pain.

It’s not just prescriptions, however. Heroin has become a go-to street drug for an increasing number of young whites of diverse income classes, according to a CDC report comparing the early part of the century to 2013. Men dominate use, though women doubled their use in less than a decade, and low-middle income earners rose most sharply compared to the rises for the poor and and middle-to-wealthy.

The Drivers

One company that has been targeted by anti-drug activists and legal authorities alike is Purdue, a pharmaceutical company that pleaded guilty in 2007 to misleading about the addictive potential of Oxycontin. A leading company in its field for decades, Purdue used relationships with doctors, databases and aggressive marketing to turn Oxycontin into a top-prescribed drug.

The company defends itself, noting that it has developed anti-addictive products and that it warns about the potential of addiction to Oxycontin. It also notes that its product is only two percent of all prescribed opioids.

Many medical professionals say a survey of patient experience has helped institute a culture of patient satisfaction instead of patient results that has led to increased prescription drugs. The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey was launched in 2006 by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and includes a number of questions about patient care. However, as described by one group of critics:

Much attention has focused on Question 14 in the HCAHPS survey, “How often did the hospital or provider do everything in their power to control your pain?” This question is inextricably linked to the “pain as the fifth vital sign” culture promoted by the Joint Commission and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality — a culture responsible for the misperception that patients should experience no pain.

The pain survey question’s critics are legion, though a top CMS official argued in Spring 2016 that the causal link between the survey and over-prescribing of drugs has not been proven. To quote Time:

CMS […] disputes any link between its surveys, a hospital’s reimbursement money and opioid abuse. In March, agency doctors wrote in JAMA that the patient-satisfaction survey accounted for 30% of a hospital’s total performance score in fiscal year 2015, with pain management one of eight equally weighted dimensions, along with factors like nurse communication and cleanliness and quietness.

But top medical researchers say surveys and other data show doctors are incentivized to over-prescribe thanks to the survey. This may also include financial incentives — Time also noted the survey as a whole (including the pain questions) is the basis for $1.5 billion in Medicare payments under the Affordable Care Act.

In June, CMS proposed eliminating the pain question “to eliminate any potential financial pressure clinicians may feel to overprescribe pain medications,” though it stated “there is no empirical evidence” the pain questions “unduly influence prescribing practices.”

CMS continues to believe that pain control is an appropriate part of routine patient care that hospitals should manage and is an important concern for patients, their families, and their caregivers. Thus, CMS is also currently developing and field testing alternative questions related to provider communications and pain to include in the program in future years.

A nurse who spoke anonymously to The Stream says that survey has caused great harm to both patients who legitimately need pain control and those who abuse it. “When you actually work in the environment with people being overprescribed pain medication because pain is not something to be questioned (if the patient says they have pain and a lot of it regardless if they are on their cellphone laughing while eating Cheetos), then we are not to question.”

Another government policy that could be causing harm is the 1986 law requiring emergency rooms that receive Medicare reimbursements to treat all people who come into them — meaning that even patients known for abusing prescription drugs are unlikely to be turned away. In 2011, 29 percent of emergency room “visits involving nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals … involved narcotic pain relievers,” yet many doctors continue to provide pain-deadening pills. A Columbia University professor and New York City emergency room doctor wrote about the problem of giving drugs to abusive patients for The New York Times earlier this year, citing both the survey and doctor preferences to simply provide pills so patients more quickly leave the emergency room.

A viral YouTube song, created by a doctor, looked at over-prescriptions, addictions, mental health and preventive care. It was praised in comments by medical professionals for its depiction of pharmaceutical companies and doctors who give too many drugs to patients who manipulate the system.

Pharmacies are also being targeted as part of the supply chain of addiction. The Attorney General of West Virginia has filed charges against two pharmacies for what he claims are violations of consumer protection laws. One of the pharmacies “dispensed nearly 1.8 million doses of addictive hydrocodone and oxycodone from 2010 to 2016 in a region of fewer than 34,000 residents in Grant, Hardy and Pendleton counties.”

Policymakers React

Throughout the 2016 presidential campaigns, and culminating in the 21st Century Cures Act signed by President Obama and passed nearly unanimously by Congress, the opioid crisis has been discussed with a focus on compassion and treatment.

Liberals have criticized the Act for calling for some deregulation, but Obama and members of both parties praised it for including cancer research, increasing mental health funding, a five million dollar increase for medical research and a billion dollars to directly combat the opioid crisis.

Much of the mental health and opioid dollars will be sent to the states in block grants and other formats for counseling and other treatments. This is the latest of a number of non-law enforcement methods meant to help addicts overcome drugs — such as needle exchange programs.

Liberals say the reaction is a welcome change from the 1980s police crackdown against the crack cocaine epidemic that devastated black communities. But some, such as Democratic Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown, say the softer touch may have a racial component.

There are differences between the crack and opioid epidemics, though the recent rise in heroin among poor whites seems akin to the crack epidemic among poor blacks 30 years ago. There are differences: crack is a stimulant while opioids are depressants, crack started as an illegal drug in the streets while opioids began in the doctor’s office, and, according to a 2006 study of the crack epidemic, crack was directly linked to increased homicide rates.

A study from the 1980s of 573 Miami-based substance abusers found that these abusers claimed that they had committed over 80,000 violent crimes.

The 2006 study found that fetal death, low birth weights, foster care and a spike in weapons arrests were also linked to the crack epidemic, though the study’s authors declare, “Our analysis suggests that the greatest social costs of crack have been associated with the prohibition-related violence,” as opposed to the drug itself. (In other words, the War on Drugs has created more harm than the drug itself.)

However, Steve Berman, a Stream contributor, says a new drug war is needed — this time, against drug companies who encourage the overuse of opiates despite the harms of addiction and overdosing.

A spokesperson for a federal agency told The Stream that two reasons for different treatment of opioids compared to crack are the intentionally different focus of the Obama administration compared to the Reagan administration, as well as greater knowledge and research on addiction.

That softer approach may not always be effective. The Stream’s Rachel Alexander recently outlined how some of Obama’s commutations for allegedly non-violent offenders put violent felons back on the street

Purdue did not respond to requests for comment about Oxycontin, while CDC survey critic Cleveland Clinic’s Dr. Jason Jerry was not available. Likewise, spokespeople for the Centers for Disease Control and the White House’s Office of National Drug Policy were not able to provide information on the differences in access to crack and opioids, nor any data on correlations or causally linked illegal behaviors for opioids (whereas the crack epidemic was linked to higher homicide rates among blacks, as seen below).

The U.S. Department of Justice also did not respond to a request for comment about criminal activity linked to opioid use.