How Christians Used to Fast, and Still Do in Some Places

On Ash Wednesday and the start of Lent, an historical look at fasting.

This is the third piece in a series on fasting. Read part 1 here and part 2 here.

Today is Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent. This is the time, historically, when most Christians fasted in some way.

These days, folks use the word “fasting” to refer to all sorts of things. We talk about juice fasts and grapefruit fasts. People will even say they are “fasting from” Facebook, email or TV.

But there are good reasons to retain the strict form of the word “fast,” which refers to food.

We Have a Word for That

Sure, words come to mean different things all the time. But we already have a good word to refer to giving up one food or activity: abstinence.

Let’s say I give up corn chips (and nothing else) for Lent. I’m making a tiny sacrifice to enter more fully into Christ’s passion. That’s fine. But I shouldn’t call it a fast. If someone asks me why I’m dipping cucumber slices in the guacamole, I can say I’m abstaining from or “giving up” corn chips for Lent. (Otherwise, I shouldn’t advertise it.)

We still need a word to refer to what Jesus did just before the start of His ministry. And what hundreds of millions of Christians have done for centuries.

Fasting means to freely abstain, that is, give up much or all food (and sometimes drink) for some amount of time. Muslims, for instance, fast from both water and food between sunrise and sunset during the month of Ramadan.

That doesn’t mean fasting is a “Muslim thing” that Christians should avoid. Religions and people feast and fast for all sorts of reasons. Jesus fasted from all food for forty days in the wilderness before he launched his public ministry. At other times, He feasted. So early Christians followed His example.

What Early Christians Did

Christians in the first few centuries were much closer to the culture and language of Jesus than we are. So, it’s easy to see where we’ve grown lax by comparing what we do with what they did.

And when it comes to fasting, they put us to shame. All the major Church fathers — including Justin Martyr, Polycarp, Clement of Alexandria and Augustine — commended fasting.

The Didache (written around AD 110), took fasting for granted. It advised Christians to fast and pray for their enemies (you know, the ones who might be trying to kill them), and to fast for one or two days before baptism.

It also sought to distinguish their fasts from Jewish and pagan fasts. The Didache advises: “Let not your fasts be with the hypocrites, for they fast on Mondays and Thursday, but do your fast on Wednesdays and Fridays.” Why those days? Because that’s when Jesus was betrayed and crucified.

Fasting for Everyone

Just because Jews and pagans fasted, it never occurred to Christians that they shouldn’t fast. On the contrary, the Church fathers often argued that fasting was intended for the whole human race, which includes Christians. They noted that God’s first command to humanity was to abstain from one kind of food. Adam and Eve could eat the fruit of any tree in the Garden of Eden except for the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. (And they couldn’t even manage to do that!)

By the fourth century, Christianity had become the official Roman religion, rather than a tiny persecuted sect. By that point, Christian fasts had become a regular part of the calendar, especially during Lent and Advent. This was wise, since fasting is much easier if it’s a group effort. That way, everyone in your social circle isn’t tempting you to break the fast. (See here, here and here for more details.)

Over the last century, however, Western Christians have grown lax. Catholics have retained the form but lost much of the substance. Many Protestants fast, but as an individual practice.

Only one Christian tradition has held firmly to the old ways.

What Byzantine (Eastern) Christians Do

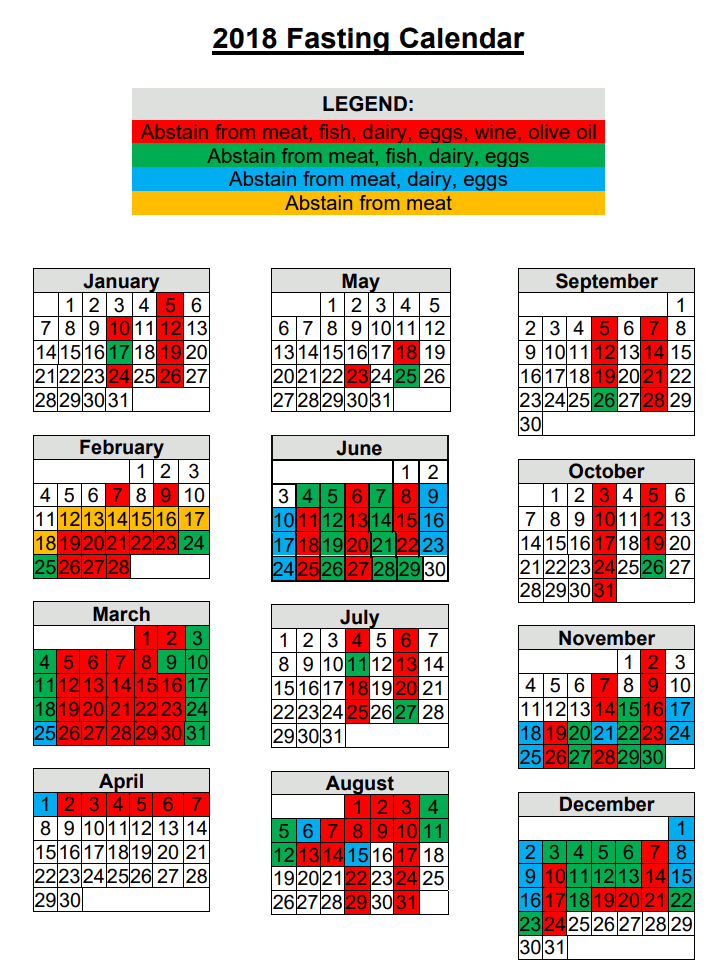

Step into a traditional Byzantine church, and it feels like stepping back in time. This group of traditions retains a much more ancient form of worship, feasts and fasts. Check out the 2018 fasting calendar of Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Rite Catholics:

This regimen is manly to say the least. There are fasts of different kinds for all forty days of Lent (not just mini-fasts on Fridays). And these get more intense during Holy Week. Look at March.

There’s another forty day fast during the weeks before Christmas.

And a month-long fast for the Apostles (including especially Peter and Paul) during June.

Also, a partial-fast every Wednesday and Friday.

And before a lot of special holidays.

Don’t worry. Young children, the ill, and pregnant women are exempt. Alas, there’s no provision for people who merely “get light headed after three hours and have to eat.”

This is not a starvation diet. Yes, there’s plenty of fasting and abstaining from different kinds of food. But there are also normal days as well as feasts when the faithful eat and drink more than they would on normal days.

When I first saw this calendar, I thought: I could never pull this off, and, frankly, I don’t want to.

I have the same thought when I read about heroic Middle Eastern Christians who freely go to their deaths, rather than renounce their faith in Christ.

You may have the same thoughts.

But maybe fasting and spiritual heroism go together. It’s hard not to notice that Christians in persecution hot spots tend to have the most hardcore fasting calendars. Coptic Christians in Egypt follow a supersized version of the Orthodox calendar above: It covers 210 days of the year, and is sometimes strictly vegan, or even water-only. The Ethiopian Orthodox have some kind of fast 250 days a year (out of a total of 365).

What about Chinese Christians? Yep, lots of fasting.

You Already Fast Every Day

I mention all this not to say we should do what Ethiopian Christians do — though it’s worth thinking about. My hope is to open up the window of options in your mind. Fasting is not nearly as hard or eccentric as you might think, if you’ve never made it part of your lifestyle.

In fact, you’ve fasted every day of your life. To fast is simply to abstain from food. If you’ve ever eaten your last meal at 7:00 pm, and didn’t eat again until 7:00 am, you’ve survived a twelve hour fast! That’s why we call our first meal breakfast. We’re breaking our nightly fast.

We don’t think much about it because we’re sleeping most of the time. To get serious about fasting, though, we can start with that first small step, one we’ve already taken. Since this is the first day of Lent, it’s a good time to start building on that baby step.

Maybe you’re still worried that fasting is bad for you. I’ll tackle that myth in the next installment.

Jay Richards is the Executive Editor of The Stream and an Assistant Research Professor in the Busch School of Business and Economics at the Catholic University of America. Follow him on Twitter.