God and Apollo 11: Can America Be Great Without God?

Today, July 20, marks the 50thanniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to step foot on the moon. In terms of technology and politics, this is one of the greatest American achievements. Indeed, it’s one of the greatest of all human achievements. It will always merit a place in those short video collages of human history.

For me, the moon landing serves as a psychological bookend. It forms one of my earliest memories. My dad tells me that we watched the landing together on TV. But I was very young, so I’ve never been sure if my memory is of Apollo 11, or of one of the later Apollo missions. In any case, the moon landings transfixed my childhood imagination.

Work of Human Hands

Neil Armstrong, as everyone knows, was the first to step foot on the lunar surface. Aldrin, who stepped down on luna firma seventeen minutes later, joked that he would “forever, no matter what I do, be known as the second man on the moon.”

But Aldrin was first in another category: He was first to celebrate Holy Communion on the moon. Aldrin, a Presbyterian Elder, recalled later in an article in Guideposts that his pastor had often talked about how God revealed himself through ordinary elements. Bread and wine, though “the work of human hands,” are not much more than plain old wheat and grapes. Yet through them, God gives Himself to us.

The act, he hoped, could symbolize “the thought that God was revealing Himself there too, as man reached out into the universe. For there are many of us in the NASA program who do trust that what we are doing is part of God’s eternal plan for man.”

“In the Beginning, God …”

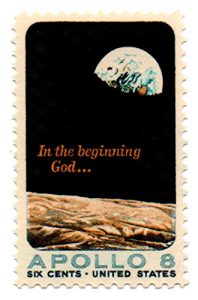

There was a similar, much more public gesture during an earlier Apollo mission. The previous Christmas eve (1968), astronauts Bill Anders, Jim Lovell and Frank Borman read Genesis 1:1-10 as they orbited the moon and gazed upon the Earth from a quarter million miles away. It was this same Apollo 8 mission that brought us the historic “earth rise” image or our planet appearing to rise above the lunar horizon.

The famous atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair unsuccessfully sued the U.S. government for allowing such a religious display. Her suit went nowhere. Indeed, the event was later commemorated by a U.S. postal stamp of the Earthrise image, which read “In the beginning, God …”

These national Christian expressions surprise us in 2019. But they were common in our country, even at the end of the tumultuous 1960s. They would hardly have been seen as partisan. O’Hair was deemed, quite rightly, as a crank. No doubt our cultural elites would now see such a televised reading of Scripture, and communion on the moon, as a sign of creeping Christian theocracy.

Loss of Faith

For many cultural commentators, the Apollo missions represent the high-water mark of American greatness. They argue that the Apollo missions were the end of an era when our country could still do great things. Despite our much greater technological prowess in 2019, it’s hard now to imagine such a unified national effort. Many have said in recent months that we could no longer pull it off.

Of course, the moon landing must be seen in context. The early space missions were spurred on by our life-and-death rivalry with a communist superpower. We took great risks and spent great treasure to get to the moon because we wanted to beat the Russians to it. And it would be another twenty-some-odd years from the Apollo 11 landing before we would defeat the Soviet Union. That was also a great achievement, and by no means inevitable.

And still in 2019, we’re hardly a backwater. The U.S. is an economic and technological colossus. We’re the sole superpower, at least for now. If we really wanted to return to the moon, we surely could.

And yet, there is still that feeling that we have lost something as a culture. That as a country we no longer aspire to great feats. If you’re like me, memories of Apollo 11 conjure up feelings of both pride and melancholy. I cannot help but think, like Buzz Aldrin, that there is a deep connection between the faith that infused and inspired our country at its origin, and what we subsequently achieved. Insofar as we as a nation have lost touch with that faith, we have lost our motive force.

Make America Great Again?

Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016, in part, by appealing to this sense of loss. “Make America Great Again” didn’t appeal to voters by suggesting that we are all losers. It appealed to voters who sensed that our past glory has been lost but could be regained.

Despite our economic and technological gains, it seems as if we have been mostly running on fumes for these last five decades. We’re drawing down the stores of cultural — indeed, spiritual — wealth deposited by our ancestors.

We might be the sole superpower, but our culture and cultural institutions seem, in many ways, feeble. While many Americans are still people of faith, the faith that inspired almost all early Americans has diminished as a public reality. Even the least religious of the American Founders spoke earnestly of the public duties we owe to our Creator. It would be hard to argue that, as a country, we still recognize that duty.

But is this decline inevitable? Surely not. If we are to regain some of our lost greatness, however, it will come, not by focusing first on inspiring feats of daring and technology, or on political victories, or space missions. It will come by renewing the faith that first made America great.