Is College Bad for the Poor?

There was a dust-up this week over a New York Times op-ed from Professor Ellen Ruppel Shell entitled “College May Not Be Worth It Anymore.” Shell is the author of a book coming out later this year called The Job: Work and Its Future in a Time of Radical Change.

The dust-up had to do with something Shell wrote about the return on investment that poor students receive from their college degrees. Shell wrote:

College graduates born poor earned on average only slightly more than did high school graduates born middle class. And over time, even this small “degree bonus” ebbed away, at least for men: By middle age, male college graduates raised in poverty were earning less than nondegree holders born into the middle class.

The Response

Shell referenced a study conducted by researchers Timothy Bartik and Brad Hershbein. But within 24 hours, both Bartik and Hershbein replied that Shell misrepresented their data. Bartik’s reply came in a lengthy twitter thread. Hershbein gave an interview to The Chronicle of Higher Education. The two then gave a more substantive rebuttal in a 3 page white paper. New York Times associate editor David Leonhardt got into it Friday with an op-ed of his own.

Why tell students from low income families “don’t go to college” when college is the very thing they need to access high paying jobs?

In a nutshell, the researcher’s don’t believe their work supports the hypothesis that the poor should not pursue college. Their research divided people into two groups: Families below and above 185% of the poverty line. Why the 185% figure? Because that’s the cutoff for free or reduced price lunch eligibility in K-12.

Bartik and Hershbein have found that if you’re above 185% of the poverty line, your career earnings are 136% higher if you graduate from college than if you don’t graduate from college. And if you’re below the 185% cutoff? You earn 71% more having a BA/BS degree versus just a HS degree. That’s less than 136% — a lot less — but it’s not terrible, and it’s not negative.

Bartik and Hershbein don’t want to be interpreted as discouraging college attendance among the poor, because a college degree (in their view) is a huge ticket to upward mobility. Why tell students from low income families “don’t go to college” when college is the very thing they need to access high paying jobs?

Should Graduation Be Assumed?

Shell does not dispute that students born into poverty, on average, benefit financially if they graduate from college. But that’s a big if, Shell cautions, tweeting, “People born poor are far less likely to be able to complete a degree. That’s a HUGE part of the problem.” And: “College is costly, and before making that investment in time and money, people should be aware. Can they afford to COMPLETE college? Without a degree, college attendance can leave them in debt and with little or no benefit.”

We’re talking about two separate things here, both of which are beyond dispute: (1) poor students are less likely to attend college in the first place; and (2) Those who do attend are less likely to graduate. How bad is it? Well, the gap between poor and rich students’ college graduation rates is larger than the gap between their college enrollment rates, says the John Hopkins Institute for Education Policy. We’ve boosted access to college more than completion.

For students from the lowest socioeconomic status (SES) background — the lowest quartile, or bottom 25% — the college graduation rate is just 14%. If you’re from a high SES background — the highest quartile, or top 25% — the graduation rate is 60%.

And If They Do Graduate?

If I come from a family that’s below 185% of the poverty line, and I do graduate from college, what then? On average, I earn 71% more than if I only had only a high school degree. That’s good. But as both Bartik and Shell would agree, this is an average. Some get a much larger boost. And others get a smaller boost — or maybe no boost.

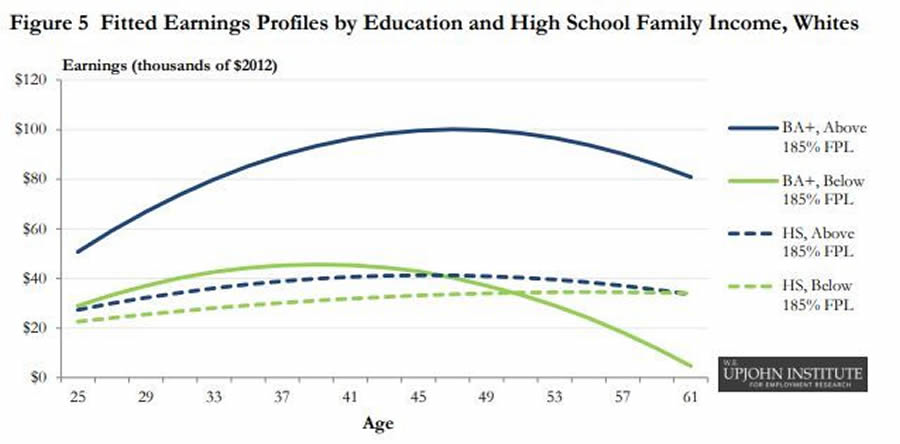

Or maybe a negative boost, over a lifetime? Here’s where things get weird. Bartik and Hershbein work for the Upjohn Institute, which published a short report with this graph:

We’re looking at whites from poor families (less than 185% the poverty line) vs. whites from non-poor families. Those who completed a bachelor’s degree (BA/BS) or more (maybe a master’s degree), they do better — for a while. Later in life, when all people’s earnings tend to decrease, they seem to do worse.

The paper observed that their sample size was small: They didn’t examine many whites raised in poverty who earned bachelor’s degree, and they tracked even fewer of them into their late career. Maybe this is what Bartik meant when he tweeted that the “data was strained” and that white men in this category “may have better options without a four year degree.” Bartik noted that “the differential returns to college with family income background occur only for men, not women, and for whites, not blacks.” For blacks, the earnings bump from college was almost the exact same whether you came from a poor or non-poor family (173% vs. 179%).

Different Levels of Access to High Earning Careers?

Bartik notes that a key reason that college graduates from wealthier backgrounds do better is that they disproportionately access careers with very high earnings. Think finance. The Ivy Leagues are filled with students from high net worth families, and their penchant for pursuing high money-making lines of work is well established. Shell noted in her op-ed that “black and Hispanic students are significantly less likely than are white and Asian students to attend elite colleges, even when family income is controlled for.”

Dr. Alex Chediak (Ph.D., U.C. Berkeley) is a professor and the author of Thriving at College (Tyndale House, 2011), a roadmap for how students can best navigate the challenges of their college years. He’s also the author of Preparing Your Teens for College. Learn more about him at www.alexchediak.com or follow him on Twitter (@chediak).