What Would Jesus Do to Nazi War Criminals?

Sometimes we should read about, and ponder, questions that make us uncomfortable.

Are you looking for a book that will change your life?

No, neither am I. I’m tempted like everyone else to find instead erudite and witty titles that confirm what I already think. But since (as I’ve learned) it turns out that such a reading plan was the exact one that Hitler followed, I’ve had to reconsider it.

Now, I’m not suggesting you start the New Year by running out and buying some radical feminist manifesto — except the really crackpot ones that are good for a laugh, and are fun to read aloud to friends over pints and pretzels. See nun-turned-witch Mary Daly’s Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism, and Valeria Solanas’ Society for Cutting Up Men (SCUM) Manifesto. Those are a lot of fun.

Read Something that Makes You Uncomfortable

No, instead I’d like to suggest you find a book that takes a sane and wholesome, even spiritual view of a deeply uncomfortable subject. So you will look with the eyes of reason and faith, but at something you’d rather not think about. Consider the topics that make you just want to turn away and switch on the television, or spend an hour “evangelizing” on Twitter.

It might be global poverty, aggressive Islam, abortion, the collapse into doctrinal mish-mash of a church you’ve always loved, or some other ugly subject. Consider whether your aversion might be a sign that you really do need to give this topic (whatever it is) some hours of your attention. Perhaps there is something you really are called to do, in your own small way, to make things better. Maybe it’s just important that you be better informed on it as a voter, parent, or general purpose Christian.

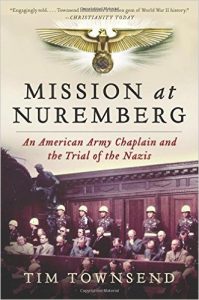

Recently I hunkered down to tackle a deeply disquieting subject: The nexus point of cheap grace, repentance and genocide. They all come together in Tim Townsend’s fascinating, carefully researched book Mission at Nuremburg. It tells the story of Henry Gerecke, a good-hearted Lutheran pastor who became an army chaplain during the Second World War, and got assigned to pastor some of the worst human beings on earth: the Nazi defendants at the Nuremburg war crimes trials. It wasn’t Reinhold Niebuhr or Karl Barth whom the American military authorities chose to interview and counsel these architects of aggressive war, eugenics programs and large scale genocide. It was an ordinary, middlingly-educated Lutheran minister from St. Louis. Most of his previous experience was with small-town Midwestern German-American farmers, and urban missions to the homeless — with some time spent in U.S. prisons ministering to run-of-the-mill criminals.

Alongside equally ordinary Catholic chaplain Rev. Sixtus O’Connor — a humble Franciscan philosophy teacher from upstate New York — Gerecke was the man whom Providence placed in the cells that held Albert Speer, Heinrich Himmler, Julius Streicher, and the top Nazi generals who survived the collapse of the Reich. Their task? From the perspective of the U.S. military which dispatched them, it was to comply with the terms of the Geneva Convention by providing prisoners with access to religious counseling and services. But Gerecke knew that much more was asked of him than that. It was his job to confront men who had risen to the top of the world — gained wealth and fame and the power of life and death over millions — by discarding the Christian vision of human dignity, in favor of a pagan fetish of a single race and nation.

Alongside equally ordinary Catholic chaplain Rev. Sixtus O’Connor — a humble Franciscan philosophy teacher from upstate New York — Gerecke was the man whom Providence placed in the cells that held Albert Speer, Heinrich Himmler, Julius Streicher, and the top Nazi generals who survived the collapse of the Reich. Their task? From the perspective of the U.S. military which dispatched them, it was to comply with the terms of the Geneva Convention by providing prisoners with access to religious counseling and services. But Gerecke knew that much more was asked of him than that. It was his job to confront men who had risen to the top of the world — gained wealth and fame and the power of life and death over millions — by discarding the Christian vision of human dignity, in favor of a pagan fetish of a single race and nation.

Treading the Tightrope Between Judgmentalism and Cheap Grace

He had to hold them accountable for their crimes, the fruits of which he’d witnessed on visits to the bloodstained cells of Dachau, where countless clergy and political prisoners had been brutalized, starved and shot. He had to be on guard against a cheap, last minute “repentance” on the part of these conquered Nazis, embraced for the sake of leniency in sentencing — or even worse, as a cynical means of evading their guilt before the fearsome judgment seat of Christ (which is, when you think about it, also a ploy for leniency in sentencing).

But Gerecke also knew that he had to minister to these men with all sincerity, to offer them if possible the chance to reclaim the Christian faith of their youth, and accept the Grace of forgiveness that Christ offers to all — even the worst of men, if they will accept it.

Townsend depicts with power and spiritual sensitivity Gerecke’s attempts to discern how sincere each war criminal is in his belated approach to the Gospel, in the shadow of the gallows.

Townsend depicts with power and spiritual sensitivity Gerecke’s attempts to discern how sincere each war criminal is in his belated approach to the Gospel, pursed under the shadow of the gallows that would claim all but a few of them. The story also highlights how spiritually beneficial capital punishment can be — in that it forces such criminals to confront the inevitability of judgment, and starkly underlines the sanctity of innocent life, by imposing the ultimate earthly penalty for profaning it. How much less likely such habitually arrogant, ideologically self-poisoned men would be to repent if instead of facing the hangman they were sitting comfortably in prison, reading fan letters from neo-Nazis around the world.

Holy Communion for Hermann Goering?

The most powerful scene in the book is Gerecke’s last interview with Hermann Goering — the most comprehensibly human among the leading Nazi criminals. Here was a man motivated not by an almost psychotic hatred of Jews — as Streicher, for instance, was.

Instead, he had lived in the grips of deadly sins such as gluttony, vainglory, and greed, stuffing his belly with the finest foods till the end of the war and hoarding stolen works of art. He didn’t detest Christianity as a Jewish plot to undermine Aryan vigor, as Baldur von Schirach had. Instead, Goering treated the Gospel with a modern, world-weary shrug, as a fable designed to console women and children.

It’s with that blasé, self-serving attitude that Hermann Goering asks Gerecke to administer him Communion. As a registered member of the Lutheran church, he claims that he is entitled to it. And he thinks it couldn’t do him any harm. It might even do him some good in case — you know, all that redemption business turns out to be true after all.

Gerecke agonizes over this, but finally sees that he must deny him. Communion given to the unrepentant is not an opportunity of grace, he remembers, but a sin of sacrilege. Rather than heap yet another sin on Goering’s impressive record, he gently shakes his head but firmly refuses. He is appalled, but not quite surprised, when Goering’s pride drives him to suicide to avoid the shame of the gallows.

At a time when my own Catholic church is agonizing over the question of Communion for those living in sexually active, non-sacramental relationships, I wish that a clear ray of Lutheran light from Nuremburg could shine on certain quarters in Rome.